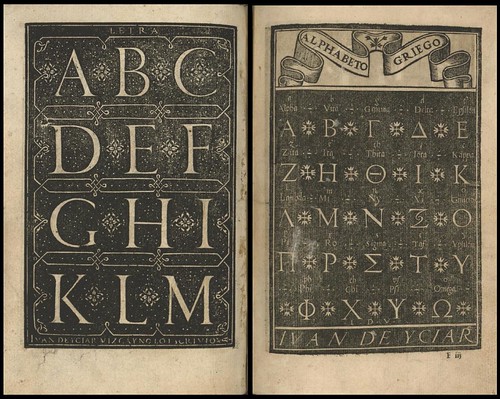

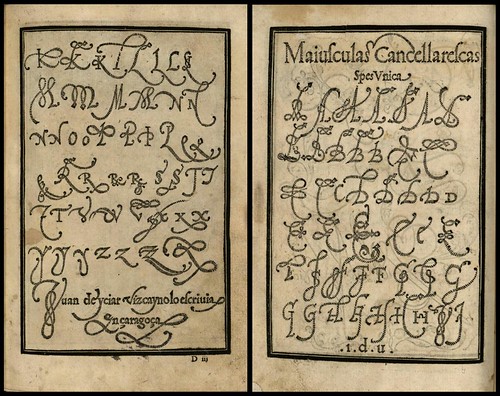

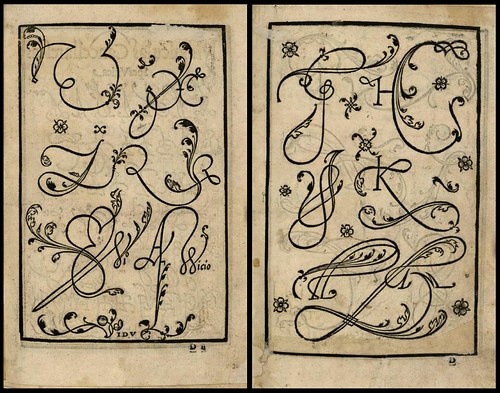

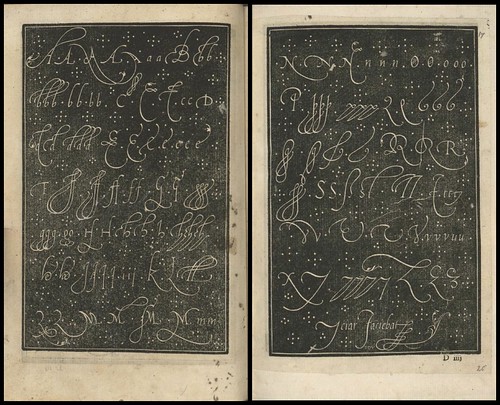

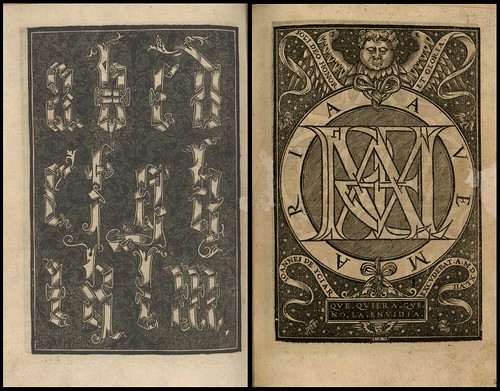

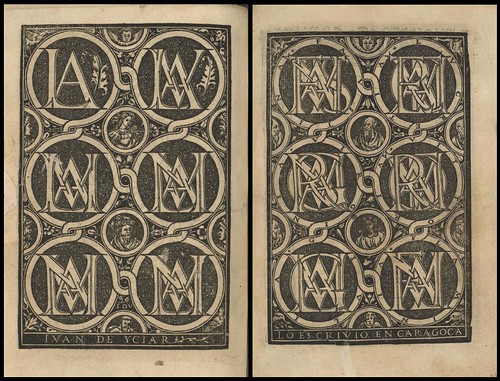

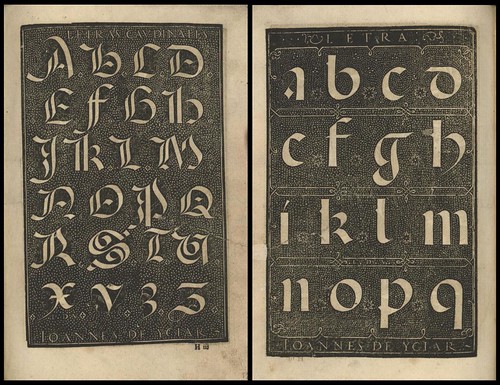

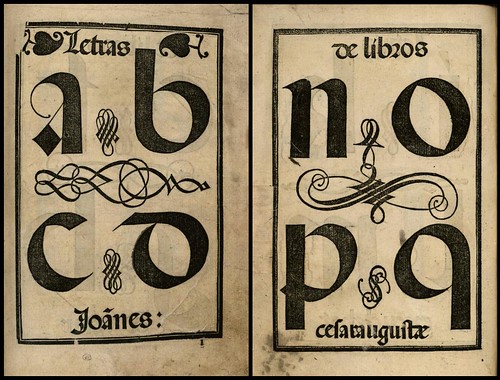

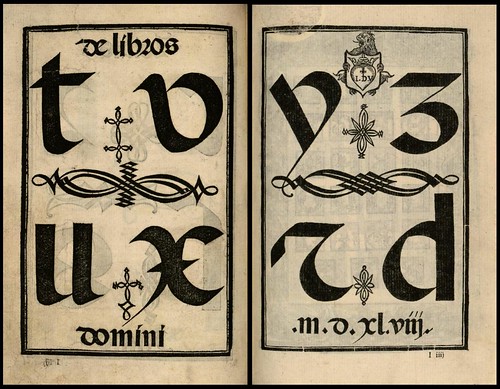

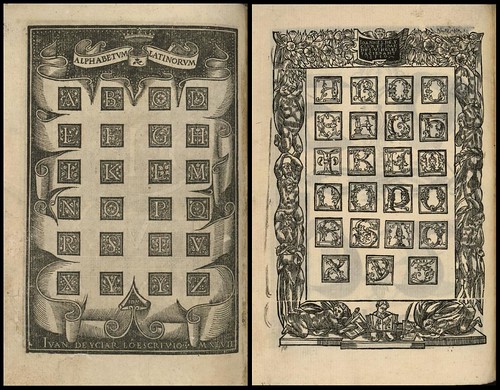

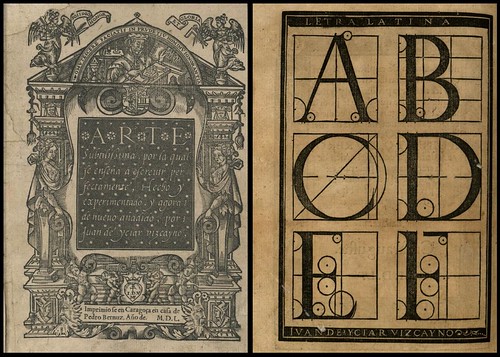

'Arte Subtilissima, por la Qual se Enseña a Escreuir Perfectamente' (The most delicate art of teaching a perfect hand), 1550 by Juan de Icíar (Juan de Yciar) with (?wood) engravings by Jean de Vingles from Lyon is available online from Biblioteca Complutense at the University of Madrid. [click on 'Láminas' in the margin for links to the illustrated pages]

To quote the Britannica Online Encyclopedia:

"From the 16th through 18th centuries two types of writing books predominated in Europe: the writing manual, which instructed the reader how to make, space, and join letters, as well as, in some books, how to choose paper, cut quills, and make ink; and the copybook, which consisted of pages of writing models to be copied as practice.

In Rome in 1540 Giovanni Battista Palatino published his Libro nuovo d’imparare a scrivere (“New Book for Learning to Write”), which proved to be, along with the manuals of Arrighi and Tagliente, one of the most influential books on writing cancelleresca issued in the first half of the 16th century. These three authors were frequently mentioned and imitated in later manuals, and their own manuals were often reprinted during and after their lifetimes.

The first non-Italian book on chancery was by the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator. His Literarum Latinarum (“Latin Letters”), published in Louvain, Belg., in 1540, was written in Latin, then the universal language of scholarship; that fact must have increased the work’s appeal to northern European scholars who associated chancery with humanist learning. Mercator expanded on the Italian teaching method of showing, stroke by stroke, how each letter of the alphabet is made; like his Italian contemporaries, he grouped letters according to their common parts rather than alphabetically.

Thus c, a, and d are presented together since they all begin with a common stroke c and are completed with a dotless i or l. His manual goes further than any previous one in presenting the order and number of strokes in making chancery capital letters. (The Italians merely presented examples of such letters to be copied.) Mercator also introduced the 45-degree pen angle for writing cancelleresca, something never suggested or practiced by Italian writing masters.

Juan de Yciar was the first in Spain to publish a copybook, the Recopilacion subtilissima (1548; “Most Delicate Compilation”). Two years later he published his Arte Subtilissima (1550; “The Most Delicate Art”), in which he acknowledged his debt to the printed books of Arrighi, Tagliente, and Palatino. Like them he showed a variety of formal and informal hands and decorative alphabets. His manual differed from theirs in its inclusion of advice for teachers as well as for students."

Juan de Icíar (~1520-1590) was a Basque painter and mathematician and the most important calligrapher of the Spanish Renaissance. He settled in Zaragoza where his two calligraphy manuals were published. His 'Arte Subtilissima' introduced the chancery script - cancelleresca corsiva - to Spain and although it is described as a copybook, it is more intended as a manual for an engraver rather than the hand scribe.

I liked a couple of small quotes by Icíar - not out of keeping in attitude towards cursive scripts from some of his contemporaries - from Jonathan Goldberg's 'Writing Matter' (1990) :

"There are some letters so unforthcoming that they refuse to enter into any sort of friendship or conversation with others" [..]

"other letters are naturally amiable and of good concord and do not deny their intimacy to any other letter".

- For a contemporary (true) copybook, see 'Libellus Valde Doctus' by the Swiss Master of Writing, Urban Wyss, from 1549 at the Culture Archive.

- A facsimile edition of 'Arte Subtilissima'

was published in 1960 and includes the original Spanish text and translations by Evelyn Shuckburgh.

- Just because I found it: 'Letter & Lettering: A Treatise with 200 Examples' by FC Brown 1921 is available from Project Gutenberg.

- Typographic resources.

- I've finally added a calligraphy tag to the delicious links {

to benow populatedshortly}.

No comments:

Post a Comment