"Repetition is not the enemy of genius, an artist can exercise

creativity by acknowledging what ought to be reiterated."

[Richard Shiff on AC Quatremère de Quincy's praise for Raphael2]

creativity by acknowledging what ought to be reiterated."

[Richard Shiff on AC Quatremère de Quincy's praise for Raphael2]

Memento Mori - Death & the Devil Surprising Two Women (source)

Soldier and Woman (etching on iron)

Landsknechte (renaissance mercenaries)

"The individualized soldier, the infantryman, made a late first appearance in the arts. Although wars could not have been fought without him, in ancient and medieval art he remained a notational cypher. He could not pay his way in the visual record, as could the centurion or the knight; but he was also absent because, unlike serving women, jugglers, friars, peasants and huntsmen, he was not wanted there.

Around 1500, in Switzerland and southern Germany, this conspiracy of silence was broken. In drawings and prints, glass painting and sculpture, the soldier emerged as a type, often strongly indivdualized; as a stereotype, familiar and real enough to bear a considerable weight of moral and allegorical resonance; and as a member of an occupational group whose appearance, way of life and relationships with comrades, civilians, and women were of avid if perturbing interest. By the end of the 1530s, artists had enabled us to know the soldier through visual evidence as we cannot know the practitioners of any other pursuit."

{JR Hale 'The Solider in Germanic Graphic Art of the Renaissance'

IN: Journal of Interdisiplinary History 1986 (85-114)}.

Officer Accompanied by Four Soldiers

Three Designs for a Fountain

On the left: Frontpiece of architecture in 3 parts: below the Holy Family, in center the Crucifixion, and above the Resurrection and the two Apostles Peter and Paul.

On the right: Arabesque with Satyrs

Venus Accompanied by Cupid Playing the Lute [see also: Lute iconography]

Three Old Women Beating a Devil on the Ground (source)

Man Embracing a Woman

Mary with Jesus (source)

Ornamental Fillet with Seahorse (source)

A Trophy of Arms (source)

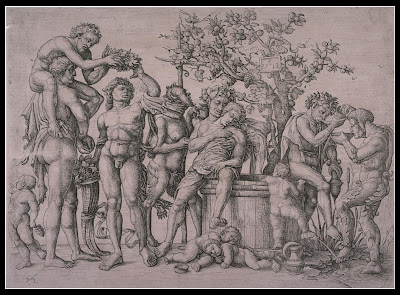

Bacchanalian Scene

Battle of Tritons

Alphabet of Roman Capital Letters with Metaphorical Ornaments

Genius or simply Ingenious?

Daniel Hopfer (~1470-1536) was trained as an arms etcher at a time when Augsburg in southern Germany was one of the main centres for the production of weapons and armour in Europe.

As circumstances would have it, Hopfer was a contemporary of some of the greatest artists in german history - Lucas Cranach, Hans Bergkmair, Hans Holbein (each known as: 'The Elder') and Albrecht Dürer, among others - who were responsible for propelling Germany, in some senses, to the forefront of the Renaissance as it emerged from Italy at the beginning of the 16th century.

Hopfer's seminal contribution to this milieu was to adapt the etching technique, that he had applied to the decorative embellishment of suits of armour for an exclusive clientele, to a reproductive printing process that could distribute his artistic output to a larger population. The attraction of this new technique (originally undertaken on iron plates) was that, whereas previously an artist was reliant upon the specialist engravers and woodcut artisans to faithfully render their artistic vision in a reproducible form, etching required little in the way of specialist skills beyond competency as a draughstman. In etching, a needle is used to draw the illustration onto a soft wax ground coating which is then eaten into the plate in an acid bath. The popularity of etching would rise to challenge both the wood and metal engraving methods.

"Although the Swiss goldsmith, draftsman and printmaker Urs Graf actually produced the first dated example of etching in 1513, Daniel Hopfer, a German artist who probably made engravings on armor, is generally credited with inventing the etching process and showing it to his compatriot Albrecht Dürer, who in addition to his other talents was a prolific engraver. Dürer became the first well-known northern artist to try his hand at the new technique, producing six etched iron plates from 1515 to 1518."The elaborate decoration of armour was most likely imported into Germany from Italy at the end of the 15th century. Rediscovered ancient Roman motifs that came to be known as grotesques as well as Islamic arabesque patterns emerged as favoured ornamental designs. Grotesques in particular, with their imaginary monsters and bizarre human figures among leafy garlands, candelabra and altars, provided a fertile decorative style for modification and reinterpretation. It was within this flux of renaissance influence that Hopfer produced both plate etchings of armour designs and armour decoration from printed illustrations. Add to this mix his fondness for emulating, modifying and borrowing from Italian renaissance art and it is not difficult to conclude that Hopfer played one of the most pivotal roles in spreading the decorative styles of the renaissance through Germany and Europe.

"On the whole, scholarship of arms etchings and other figured and ornamental arms decorations is still in its infancy. While Hopfer's contribution as a printmaker is generally acknowledged, his arms etchings are at least as important, and, like his prints, reveal the role that Italian ornamental motifs had on his transformation from a Late Gothic to a Renaissance artist. The etched motifs on the horse armour in the Landeszeughaus, for example, which were created shortly before 1510, show this important transition [figure 10]. Here he mixed intricate and fanciful Late Gothic foliate tendrils with Italianate fruit festoons that are clearly Renaissance in character."1It was common practice (and not regarded particularly as a negative phenomenon) in the early 16th century printing environment for workshops to engage in various forms of copying: replication, imitation and hybrid adaptations. Creating and circulating printed images facilitated the spread of visual information and helped accelerate stylistic changes. And artists, who had close relationships with the workshops, probably encouraged these activities so that their works were reaching a wider audience. Hopfer had married into a family of printers so it's not surprising to find that he often (but not always) copied, borrowed from or modified works by Dürer, Mantegna, Antonio Giovanni da Brescia, Marcantonio, Flötner, Cranach and others in producing his etchings. Although he favoured illustrating decorative motifs, as can be seen in the sample images above, Hopfer's etchings incorporated visual elements from a wide variety of both religious and secular subject matter.

"By working in and between different media, Hopfer facilitated the expansion of the Power of Women topos from the margins of etched armor into the center of repeatable works on paper, demonstrating the versatility of this theme concerning sexual morality and social heirarchies and its appeal to various kinds of markets"2

- Unless otherwise stated, all the images above (click for large versions spliced from screencaps) were obtained from the outstanding Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco site.

- 2Although only a modest extract is available for free, Freyda Spira's University of Pennsylvania (History of Art) 2006 dissertation, "Originality as Repetition / Repetition as Originality: Daniel Hopfer (ca. 1470-1536) and the Reinvention of the Medium of Etching" was a primary source for much of the information recorded above.

- 1'Arms, Armor and Fine Arts' © Peter Krenn is a great overview article at the MyArmoury site - it is definitely worth (painlessly) joining to view larger versions of images (among other things). They seem to have quite a selection of resources as well.

- Bildinex have a number decorated portraits (mostly), by Hopfer.

- The Schleswig-Holstein Museum have a small number of Hopfer illustrations.

- Articles from the Metropolitan Museum's Timeline History of Art: 'Arms and Armor in Renaissance Europe'; 'The Decoration of European Armor'; 'Techniques of Decoration on Arms and Armor'.

- Daniel Hopfer at Artcylopedia.

- 'What is a print?'/History of Printmaking.

- The modest 'Early Modern Painter-Etcher' exhibition site at Smith College Museum of Art and New York Times review.

- 'The Magic World of the Grotesque' catalogue review via MrH (see: Faces of the Grotesque and Clovio and the Farnese Hours)

- Out of a mixture of curiosity and interest: informal lecture notes from a current 'History of Prints' course at the University of Central Florida (Dr F Martin); George Goodall's history of books and printing timeline at Facetation; chronology of 1501 to 1600 (incorporates literary/artistic/political events)

- The Daniel Hopfer article at wikipedia is ok.

No comments:

Post a Comment